Digitopia Holographic LED Screen: High-Transparency Displays with S...

In a world where immersive experiences are redefining how brands engage audiences, Digitopia’s Holographic LED Screen stands out...

Tips, strategies, stories, and tools—everything you need to stay ahead in the industry.

In a world where immersive experiences are redefining how brands engage audiences, Digitopia’s Holographic LED Screen stands out...

Modern museums are more than spaces to preserve history — they are cultural landmarks that blend architecture, storytelling,...

As technology continues to evolve, LED displays have become one of the most powerful tools for advertising, branding,...

Digitopia’s STJ Series Transparent LED Film Displays are designed for sleek, modern applications such as glass facades, retail...

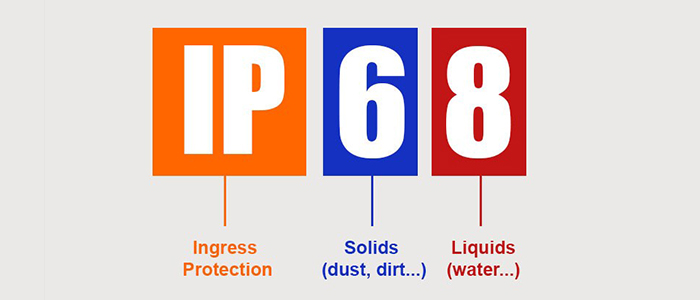

The arrival of COB (Chip-on-Board) technology marks a major leap forward in LED display innovation. Compared to traditional...

In today’s fast-paced, highly competitive world, businesses need more than traditional advertising to stand out. One powerful way...

As technology evolves, audiences expect more than static visuals — they crave immersive, interactive experiences. To meet this...

Broadcasting studios demand displays that deliver exceptional clarity, color accuracy, and reliability under fast-paced and high-pressure conditions. To...

In today’s Digital Out-of-Home (DOOH) advertising landscape, grabbing attention in crowded urban environments requires more than just a...

When evaluating an LED display, you’ll often come across technical terms like pixel, pixel pitch, and real vs....

An LED display is more than just pixels and brightness — it is a long-term investment. Whether used...

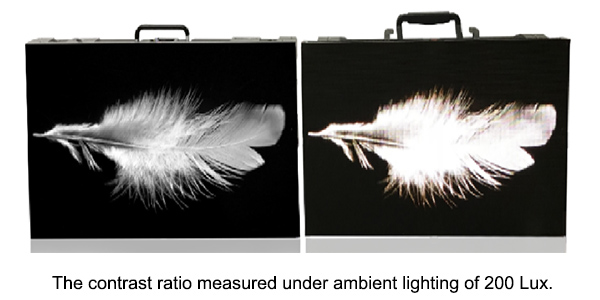

When choosing an LED display, many buyers look first at brightness or resolution. But true image quality depends...